The first four or five cottages have been renovated and scientists or work parties live in them while working in St. Kilda. The scientists watch and record the local sheep, for example, all the sheep living in Kilda are wild, don´t get fed and are called Soay sheep.

They are pretty tiny and curious like all sheep are. Find here more about “The Soay Sheep Project”

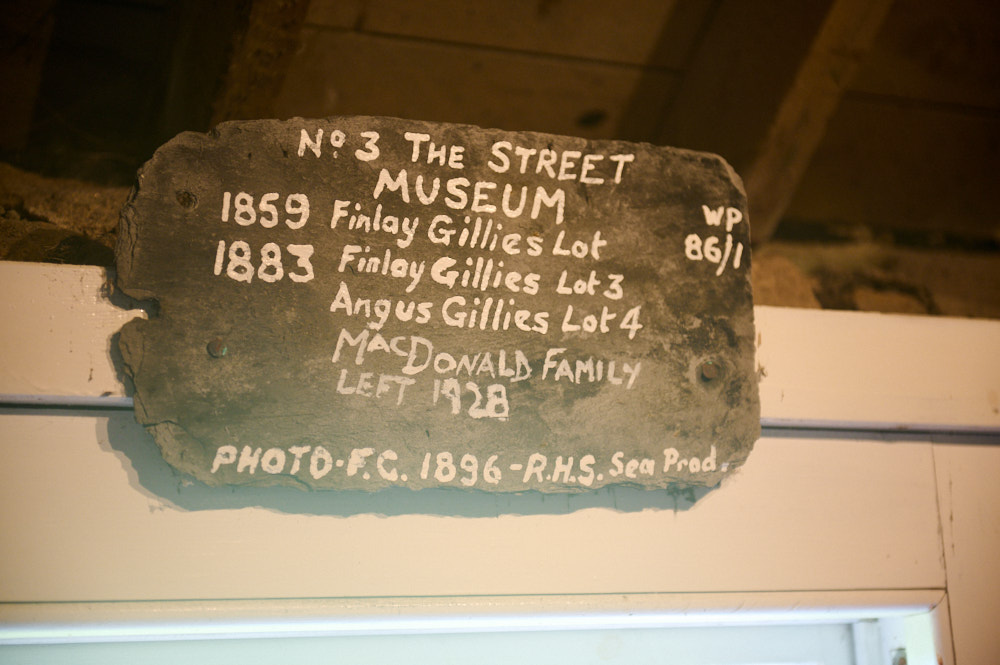

One of the cottages houses a small museum, showing how the cottages used to look and some artefacts and memorabilia.

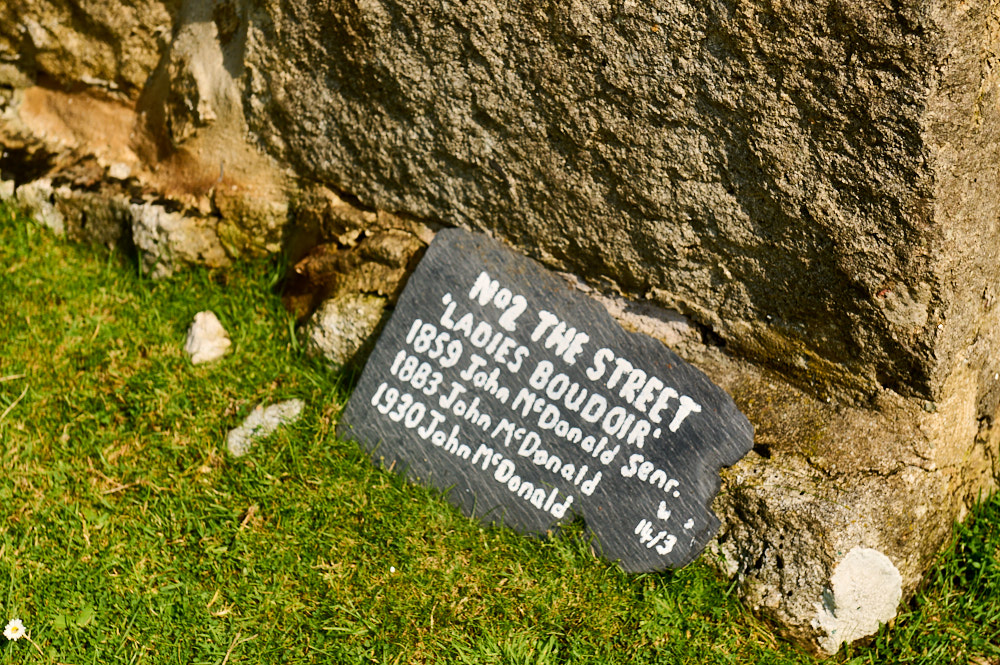

Signs tell us who used to live in a cottage.

It was fun walking through the village, meeting the anniversary ladies and it felt somehow like discovering three different timelines – the 1930ies – fifty years ago, hearing the stories the ladies tell about their time in Hirta in the 70ies – and then today.

A lot of the cottages still have the remains of the old blackhouses next to them.

The village as we see it today was laid out by the Reverend Neil Mackenzie in the 1830s and consists of a crescent of houses with associated cultivation plots, all within a head dyke. The houses built in the 1830s were typical Hebridean blackhouses – single-roomed, with the cattle being accommodated inside them in winter. In the 1860s new houses were built. These were of a standard Hebridean design with an entrance lobby, small closet behind, and two main rooms. (National Trust for Scotland)

Every morning the men of St Kilda met and held “parliament”, meaning they talked about what had to be done and who would do it. Have a look at this photo here, showing the men of St. Kilda.

The people of St Kilda, a Gaelic-speaking population, lived under their own form of democracy with an informal meeting held every weekday morning in the village street. It was known as the ‘St Kilda Parliament’ and consisted of all the adult males on the island. There were no set rules, no chairman and the ‘members’ arrived in their own time. Once assembled the ‘parliament’ considered the work to be done that day according to each family’s abilities and divided up the resources according to their needs. Everything was done for the common good. Women had their own informal meeting. (ambaile)

Village Life

The Kildians worked the land, but the main staple of their diet was seabirds. Fulmars, gannets and puffins were being eaten for most daily meals – even breakfast! Every part of the bird was used, including the meat, oil and feathers. Fish was rarely eaten even though the sea around the islands are full of them, but the Kildians preferred the birds and disliked the taste of fish.

The St Kildan had developed a unique existence, based entirely around what was available to them in and around Hirta. Each life-giving element in this subsistence lifestyle provided a crucial link, supporting a delicate balance of survival, with each part giving strength to the next. Ultimately, what these well-meaning incomers did, was unravel an age-old system of living. (Shetland with Laurie)

From the 19th century, St Kilda was visited by tourists in the summer months. The islanders offered their tweeds and also bird eggs for sale.